Masonic Aprons are one of the most interesting, beautiful and curious items in the Fraternity’s history. Members of medieval, operative stone-masons’ guilds wore large animal hide aprons, providing them with as much protection as possible from the sharp rock shards with which they worked.

Early Masonic aprons were similar, but in the late 1600s, men began to join the guild who were not actual stonemasons, but who were “Accepted” into the Fraternity nonetheless, and it is they who may have introduced the practice of decorating their aprons.

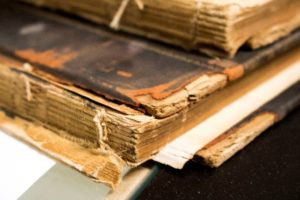

Worshipful Harry Rylands, Past Master Lodge No. 2, and Past Grand Steward, wrote The Masonic Apron (Research Lodge Quatuor Coronati No. 2076, Transactions Volume 5, London, England, 1892). In this important, early analysis of the Masonic Apron, he states, “The bordering with ribbon and decorations were, I think, introduced by the Speculative Masons, and may perhaps have been a mark of distinction.”

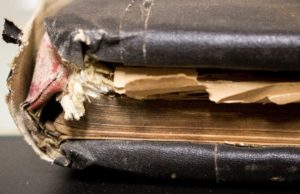

White leather was mentioned as the material for the Aprons in the Book of Constitutions, which outlined various colored silks that were allowed to be used as lining, a regulation repeated in the editions from 1739 up to 1784. Linings protected the clothing from white marks from undyed leather.

Aprons began to be much smaller, as the Lodges began to be filled with more speculative rather than operative Masons. The flap, which was previously held up with a button or a thong passed around the neck, for increased protection, or which hung loosely down, was folded over intentionally and tied around the waist.

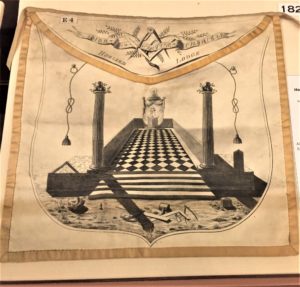

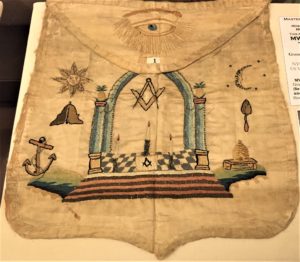

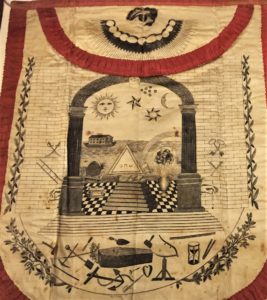

From 1760-1770, in line with the advance of printed pottery and engraved summonses, the aprons became more decorated. “As jewels, differences of rank, and other matters increased in number, so the taste for symbols and the decoration of aprons advanced, and they became more and more ornate.” (Rylands, 1892)

By 1786, Aprons were much smaller than the old aprons that went almost to the ankles. They were often ornately decorated with any number of symbols, and were diverse in size, material and decorative elements. Spangles, sequins, bullion fringe, embroidery, three-dimensional items sewn on, paint, engraved prints, engraved prints which were painted … almost anything was used in Masonic Apron decoration and design.

The Concordant Bodies of the York Rite and the Scottish Rite also began to distinguish themselves with various apron styles.

In 1814, the United Grand Lodge of England ordered a general uniformity of design and lining color.

Uniformity in the Masonic Apron shape and design didn’t take hold until after the 1840s, and, while there are distinctions in color and symbol, the wide variety of earlier days diminished and has mostly disappeared from the Masonic world.

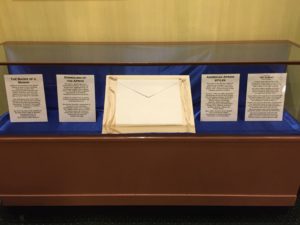

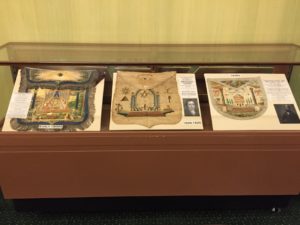

The Grand Lodge of New York holds an incredible collection of early Masonic Aprons. Some of this collection can be seen in the Library’s Online Museum by clicking here. (Please click “Browse” above the thumbnail panel in order to see the entire Fabric sub-collection.)

Next week, a brand new Apron exhibit will be installed on the ground floor of the Grand Lodge of New York’s Masonic Hall, and we invite you to visit and see these amazing works of art which reflect so much meaning and history.

References: Rylands, Harry, “The Masonic Apron”. Transactions of the Lodge Quatuor Coronati, Vol. 5, 1892. Photographs by Catherine Walter.